Material burning characteristics have changed, so it is time to change the building code.

Author: Bob Turley

Recently, three children perished in a house fire on Sandy Lake First Nation in northern Ontario. A CBC news report said the victims were aged nine, six, and four. The statement said, “firefighters, police, and community members acted quickly to try to help, but the house was already engulfed in flames.” The article says only one water truck was available to feed the fire truck, along with a lack of adequate water lines and infrastructure preventing the use of fire hydrants.

Another recent CBC headline read, “3 children found dead in Brampton, Ont., townhouse fire”. This article says, “Brampton Fire Chief Bill Boyes said firefighters encountered heavy flames and smoke when they arrived at the scene. The three children were pulled from the home and rushed to hospital, but they were later pronounced dead”.

So, what are the similarities and differences between these two incidents? Sandy Lake First Nation is a community with around 2,000 people, and Brampton has a population of about 600,000. Both communities have fire departments, with Sandy Lake protected by volunteers and Brampton protected by career staff. In Sandy Lake’s case, one news report suggests problems with fire hoses and water supply, but there were no suggestions of water supply issues in Brampton. It is reasonable to assume Sandy Lake had limited numbers of firefighters to draw from based on the single-engine response. At the same time, Brampton probably responded with 4 or 5 pieces of apparatus and 20 plus firefighters.

As far as saving lives goes, both departments had similar outcomes likely stemming from a similar cause- the time from ignition to flashover overtaking fire department response times. Flashover is the point in a fire when all combustible materials in a room are heated to their ignition point. The flashover is violent and includes exceptionally high heat energy that will even overwhelm firefighters’ protective clothing. After the flashover, all the fuel in the room is on fire, and the chance of human survival is negligible.

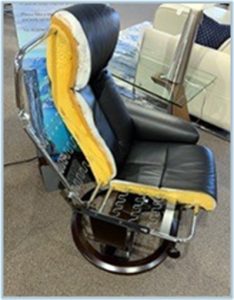

The time to flashover has changed dramatically over the years with modern synthetic furnishings. Now polyurethane foam is widely used in soft furnishings such as mattresses, chairs, and sofas. As can be seen in this photo, polyurethane foam is the leading synthetic component of most modern furnishings.

The time to flashover has changed dramatically over the years with modern synthetic furnishings. Now polyurethane foam is widely used in soft furnishings such as mattresses, chairs, and sofas. As can be seen in this photo, polyurethane foam is the leading synthetic component of most modern furnishings.

When ignited, polyurethane foam produces carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and other toxic products on decomposition and combustion, which can quickly incapacitate anyone breathing the smoke and other products of combustion. The toxic products created by burning polyurethane foam are described in this article.

When burning, polyurethane also produces much more heat energy than older natural products like kapok, which was widely used as stuffing in older furnishings.

Years ago, it was common to have flashover occur after about 10 to 20 minutes from the time of ignition. New furnishing can cause flashover in less than 3 minutes, and during full-scale test fires, some rooms reached flashover in under 2 minutes.

There are no lives for the fire department to save when this happens. The people are dead before the firefighters leave the station.

How well a fire department is trained, equipped, or staffed has little to do with saving lives in the room or area of fire origin. The more critical life safety factors are early fire detection, getting the people out of the fire area quickly (adequate exiting) and containing the fire to the room of origin (fire separation). Early detection with smoke alarms and fire separations in residential occupancies are practical tools to accomplish this. Fire separations are building components, including gypsum boards and doors designed to slow the spread of fire and smoke in the building.

Another method to slow the growth and spread of fire is to sprinkler the building. Sprinklers do not replace the need for fire departments, but they can save lives and property by reacting quickly in the early stage of a fire. Sprinklers can slow or prevent the fire from growing, allowing time for the fire department to arrive and extinguish the fire.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) is a global self-funded non-profit organization devoted to eliminating death, injury, property, and economic loss due to fire and other related hazards. Their research shows working residential fire sprinklers control fires 96% of the time. When sprinklers are present, people are 81% less likely to die in a home fire, and property damage is reduced by about 70%.

The cost of installing home sprinkler systems varies, but most estimates are between $1.50 to $2.00 per square foot for new house construction and between $2.00 and $7.00 per square foot for retrofitted systems. These costs represent a minor amount of money compared to the loss of lives and property these systems could save.

If we want to save lives, building and fire codes should require the installation of sprinkler systems in all residential buildings. There is a long history of opposition to residential sprinkler systems from building contractors and affordable housing advocates. Still, there are opportunities to use similar strategies as is being used to improve the energy efficiency of homes. Safer homes and the reduction of preventable deaths from a fire are things everyone should get behind.